WORDS FOR PICTURES

One Suitcase Per Person

Daytime somewhere in a North American city street. A neatly dressed, clean cut Asian man of around thirty years old, is photographed in mid-stride. A couple walk to his right, just beyond the range of his peripheral vision. The man, white, bearded, also in his thirties and dressed in a strange combination of denim and ‘slacks’ pulls his face into a sneer, his finger dragging his eyelid into a slit as his oblivious girlfriend trails behind him. My first encounter with Jeff Wall’s Mimic provoked an emotive reaction embarrassment, discomfort and fear. After living in Hong Kong as an adult for over ten years, Mimic confronted me with memories of similar experiences whilst growing up in England, my country of birth, and by definition, my home. When subjected to such unsolicited hostility, the defensive strategies adopted by my peers ranged from mute acceptance to attempts to jettison all traces of what made them different physically and culturally from the majority. Others sought to validate their de facto ‘Chineseness’ by acquiring knowledge of the language, history and culture of China. One Suitcase Per Person considers the strategies adopted by the artists David Diao, Ken Lum and Hiram To, all of whom have spent the greater part or an extended part of the lives as immigrants. Using the metaphor of the exigent One Suitcase, if left with no alternative, how would we define ourselves?

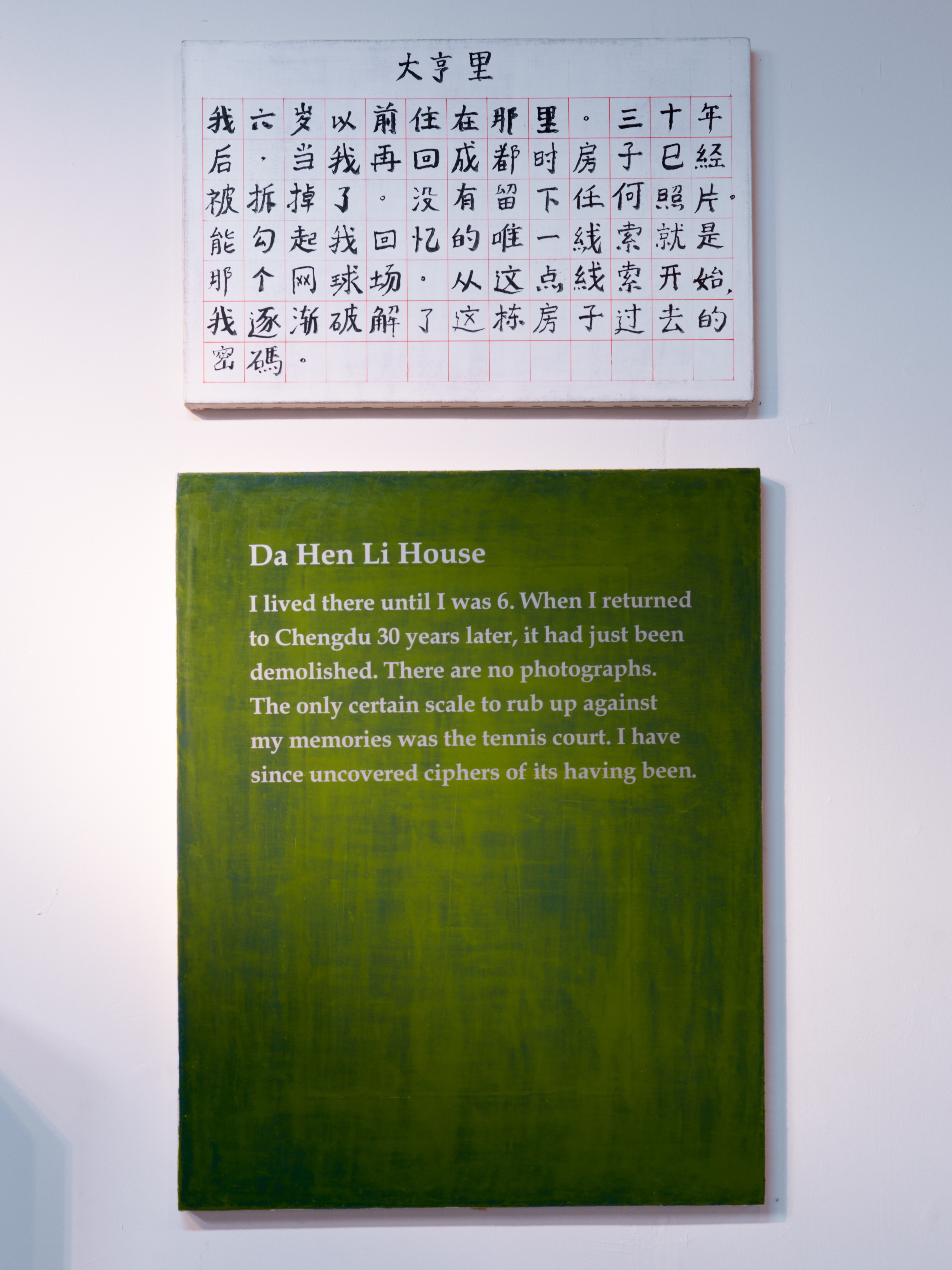

David Diao Da Hen Li House

David Diao

David Diao

David Diao’s complex body of work is distinctive for its rigorous interrogation of the critical discourses surrounding art. His bold and highly analytical paintings occupy an uneasy ground, forming a persistent critical presence within the very art system of which he is a part, questioning the shifting debates surrounding originality and authorship, modernism and post modernism and the politics of identity and ethnicity. In the context of the latter, Diao’s Da Hen Li House series of paintings form a personal and emotional counterpoint to his trenchant earlier works such as Imperiled, (2000) and Pardon Me Your Chinoiserie Is Showing (2003) that confront the ‘essentialization of ethnic identities’ a discourse alluded to in Ken Lum’s 2008 essay A China Portal. Da Hen Li House refers to the artist’s childhood home in Chengdu, which he left at the age of six and never saw again. Visiting the artist at his studio in New York, I was shown a small photograph of the artist as a solemn child of around four years old, seated next to the family dog, surrounded by the traditional architecture of a Chinese courtyard home. Too young to recall the incident or the house, Diao’s meticulous, spare and precisely executed paintings are an imperfect recollection the family home and its physical dimensions based on anecdotal recollections and blueprints drawn from memory by an uncle. By the time Diao had the opportunity to visit China, reuniting with family members after decades of separation, the house had already been destroyed. The works also recall the emotional loss of separation and how, despite the elapse of time and distance, the house continued to intersect with events in the artist’s life. Examples include how the family home included the modern Western innovation of a tennis court, and how, years later, the artist’s father passed away while playing tennis thousands of miles away; how, after the family fled, the house became the headquarters for the Sichuan Daily, the newspaper edited by author Jung Chang’s father whose activities were later described in her book Wild Swans. When pressed further on what gave rise to such an uncharacteristically personal and emotional body of work, Diao admitted that for fifty years Da Hen Li House had been a presence in his life, giving rise to the devastatingly simple realization that “everyone has lost a home”.

Ken Lum Schnitzel Company

Ken Lum

Ken Lum

Highlighting the employee-of-the-month schemes intended to encourage friendly competition and provide incentives for employees in jobs where the prospects for promotion are non-existent, Ken Lum’s Schnitzel Company pointedly invokes the attempts by corporate giants to rehabilitate themselves as ‘caring’ companies through corporate social responsibility and diversity. Emulating the branding and brash corporate colours of global fast food chain restaurants, these model employees of the month, dressed in yellow and red and identified by name and month are divested of their identities in a process that neutralises individuality into a bland corporate homogeneity. Photographed from identical angles using identical backgrounds, wearing identical uniforms, Lum’s smiling employees are psychologically unreadable, bereft of individuality despite their racial differences, appearing to have forsaken their personalities for a McJob. Schnitzel Company can be also seen to engage with the wider problematic rhetoric of multiculturalism, the pursuit of cultural diversity and tolerance of cultural difference through political policy, and the collective anxiety that has led to such policy being declared a failure by some, including Britain’s incumbent Prime Minister David Cameron. Indeed, works such as Lum’s 2002 work Sandhu’s Maple Leaf which takes the form of a billboard announcing “CLOSING FOREVER DROP DEAD CANADA” attest to this perceived failure, translating its terms into fictitious narrative. In his essay A China Portal, Lum argues:

…in spite of the painful realities that often accompany the experience of migration, it is necessary to acknowledge the shifting contemporary definition of the migrant, in order to see all that may be possible in terms of the empowerment of the individual defined as a migrant.

In the midst of such systemic change, Schnitzel Company is compulsive justification for the need to reconsider the definition of the migrant.

Hiram To Fortune Landscapes

Hiram To

Hiram To

Hiram To’s Fortune Landscapes reference Soldier of Fortune, Hollywood’s first film shot on location in Hong Kong. The work considers the erosion of the distinction between the city itself and the Hong Kong of Hollywood cliché that suffocates the city with a form of self-induced chinoiserie. In Fortune Landscapes the artist adopts the dual viewpoints of an outsider observer and of an insider regarding a Hong Kong that never ever existed. For To “the work is as much about how the ‘outside’ forms perceptions of the East, as it is about how ‘we’ play-act specific ‘stereotypes’ in defining our own identities.”

Casual Victim, a work dating back to 1990, takes the form of a model’s composite card and depicts the artist styled and photographed waiting at Barker Road Station along Hong Kong’s Peak Tramway. The designer clothing worn by the artist/model and the Club World plaque he carries aspire to the “…champagne dreams, caviar wishes…” inscribed on the back of the work, a quote from the 1980s television series Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. Barker Road Station is also the setting for the pivotal meeting between the leading actors of Soldier of Fortune, the Hong Kong of Fortune Landscapes, layering hackneyed images of the harbour and extinct fishing junks, universally acknowledged signifiers for the city, with details of flower arrangements, culled from vintage template cards of Japanese Ikebana floral arrangements belonging to the artist’s mother. In a visual sleight of hand, visitors are engaged in the act of regarding their own muted reflections as they view the work, unwittingly perpetuating the fiction caught within the Fortune Landscapes.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most apt and concise explanation for the complex and highly diverse nature of the works of these three artists may be found in a passage from writer Salmon Rushdie, quoted by Lum in A China Portal:

The effect of mass migrations has been the creation of radically new types of human being: people who root themselves in ideas rather than places, in memories as much as in material things; people who have been obliged to define themselves—because they are so defined by others—by their otherness; people in whose deepest selves strange fusions occur, unprecedented unions between what they were and where they find themselves.

As “people who have been obliged to define themselves” the works of Diao, Lum and To are a provocation, not necessarily an equal and opposite reaction to the intolerance, hostility and racism evoked in Wall’s Mimic, but nevertheless a complex and at times ambivalent response to the experiences and impressions gained from lives lived as part of a minority culture. Whilst some would discern an undoubted fluidity and to a certain extent interchangeability to the nature of identity, it is perhaps attempts such as these to rationalize the influence of cultural circumstance and upbringing that throw identity into sharp relief.

Davina Lee

Curator

© Davina Lee 2011

Published on the occasion of the exhibition One Suitcase Per Person held at 1a space, Cattle Depot Artists’ Village, Hong Kong, November 2011.